How Arts and Cultural Organizations Can Consider Adapting

Executive Summary

Aimed at helping arts and cultural organizations consider key questions and variables as they plan for reopening and a post-COVID-19 future, this report estimates the pandemic’s effect on the nonprofit arts sector and identifies three critical propositions and four prompting questions for consideration.

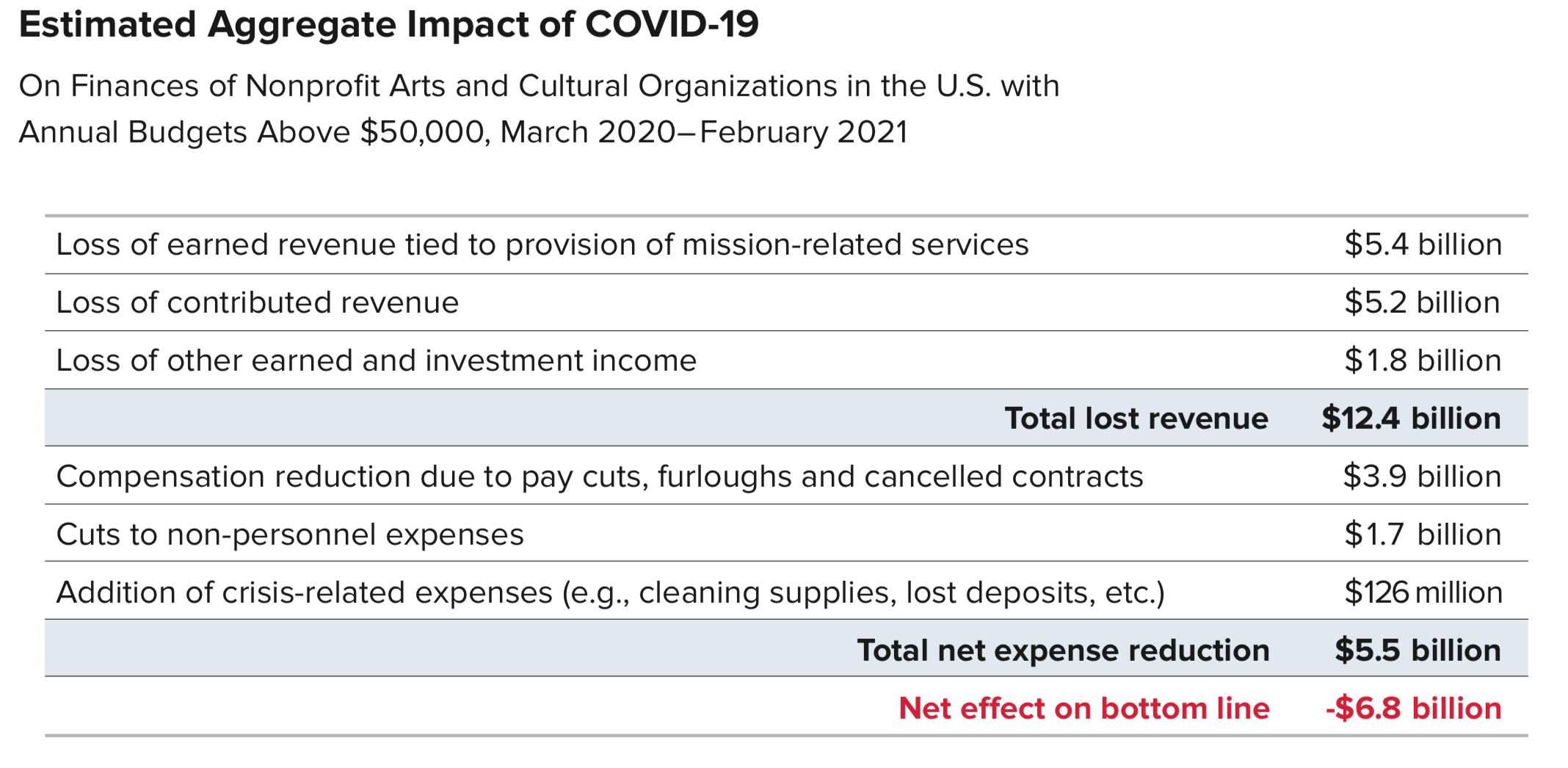

Our estimates draw on historical financial, operating, and attendance data, as well as reported near-term decisions and impact to date.[2] The estimated aggregate -$6.8 billion net effect of the COVID-19 crisis on the nonprofit arts and culture sector equates to a deficit equivalent to 26% of expenses for the average organization, over the course of a year.

This report underscores that COVID-19 has created unprecedented challenges and proposes specific steps that can be taken to address the crisis while orienting toward sustained action and resiliency. These steps reflect three propositions that any organization can develop and align in order to achieve success: its value proposition, revenue proposition, and people proposition. We argue that these steps have the potential to differentiate the organizations that not only weather the crisis but grow through it.

The report recommends that each organization consider these four questions:

- What might the next year look like? Organizations that evaluate clearly their fixed costs, adaptive capabilities, cash reserves, community ties, and relational capital will approach planning with greater odds of addressing positively their survival and revival.

- What is the source of our strength? What do we do that is most meaningful and relevant to the community? Organizations that shift focus outward to communities will build stronger ties for a post-COVID-19 revival. How an organization carries out its purpose should vary over time as it innovates in response to changing community needs.

- How will we manage our people and revenue propositions to confront the new reality? Engaging artists, staff and board members in scenario planning, experimenting with new ways of working, and innovating new ways to generate income will be required for growth.

- When our doors reopen, whom will we gather? Resilient organizations will be those whose work is meaningful to a sufficiently large segment of the local community that cares whether it exists. Reopening will be an opportunity to send a signal about the role the organization wants to play in the local community moving forward.

This white paper is designed to help organizations think through these questions to withstand the current and future challenges.

We are grateful to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for facilitating contact with the following national service organizations, which generously provided data from their member surveys: Theatre Communications Group, Association of Art Museum Directors, Association of Performing Arts Professionals, the League of American Orchestras, Chamber Music America, The International Association of Blacks in Dance, and First Peoples Fund.

This Report Comes with Free Discussion Guides for Arts Leaders

For self-guided discussions or discussions virtually facilitated by SMU DataArts.

___________________________________________________

“I saw a future, and it was like watching this tornado in the distance, just watching it come and not being able to do anything about it. I think all artists have foresight. The work that we do is to create futures and invite people into them. And so that’s what I’m trying to do: to put forward a proposal for the future and invite people into it.”

– Jaamil Olawale Kosoko[2]

Like nearly every sector of business and society, nonprofit arts and cultural organizations have been hard hit by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and the effects will continue beyond the moment when stay-at-home orders are lifted and businesses are allowed to reopen.

The lives and livelihoods of people who create the artistry that drives 4.5% of U.S. GDP (National Endowment for the Arts 2020), as well as those in the communities they serve, have been devastated by the crisis. Recovery will be slow, not only because it will take time to restart programming with diminished staff levels but also because the world as we knew it has changed. The pandemic has taken a tragic toll on human lives, altered public perceptions about the safety of gathering and sharing cultural experiences in closed spaces (Dilenschneider 2020a), and is jolting the global economy into a sharp recession (Gopinath 2020).

Cultural organizations’ strategy and structure will have to adapt to these environmental changes. The field of nonprofit arts and culture is unlikely to return to its pre-COVID state for the foreseeable future, if ever. “Business as usual” will mean something different. Seeing ahead to what that “usual” will look like is obscured by the current environment’s complexity, dynamism, resource scarcity, and uncertainty.[3] And yet the ability to innovate and reconfigure are critical when the environment is both dynamic and hostile (Frank, Güttel, and Kessler 2017).

Change will happen, for better or for worse. Those who have the bandwidth to think beyond near-term survival have an opportunity to contemplate the organization’s core values, strengths, and purpose coming out of this crisis. What is the world we want to see created as we move from not-normal to next-normal (Sneader and Singhal 2020)?

As we move from the initial reaction to sustained action, there are specific ways that organizations can consider adapting. These steps have the potential to differentiate the organizations that not only weather the crisis but grow through the crisis. These challenging times call for a move in energy away from desperation and defeat and towards passion for the communities that organizations were formed to serve (Bruch and Ghoshal 2003).

Each organization will want to consider these questions: What might the next year look like? What is the source of our strength? What do we do that is most meaningful and relevant to the community? How will we manage our people and revenue propositions to confront the new reality? When our doors reopen, whom will we gather?

We explore these questions in more detail in the sections that follow.

What might the next year look like?

Research shows that during the Great Recession, working capital, subscriptions, attendance, and corporate giving were areas that incurred permanent scarring, never to return to their pre-recession levels (Voss, Lasaga and Eyring 2019). This vulnerable state marks the starting place for many organizations heading into the pandemic. The average arts and cultural organization held less than two months of working capital pre-crisis, during a healthy economy (Thomas and Voss 2018). Not all of our beloved organizations will survive this crisis, irrespective of their size. Those with underlying issues heading into it, such as negative working capital and declining participation, are most susceptible to insolvency. Those that headed into the crisis with relatively lower fixed costs, adaptive capabilities, cash reserves, strong community ties, and a solid store of relational capital with a base of repeat customers and funders have greater odds of not only surviving, but reviving.

Many culturally specific organizations are particularly at risk, not because they are less effective or relevant than their peers, but because they tend to have less access to available cash (Voss et al. 2016). This includes in-house liquid resources and credit line limits. The first round of the federal government’s Payroll Protection Program loans that were part of CARES Act funding largely eluded small businesses without strong banker relationships, as they did black-owned small businesses.[4]

Moreover, culturally specific organizations are more prevalent in sectors that have lower average budget size (e.g., community-based arts, dance, arts education, multi-disciplinary presenters), and less prevalent in sectors with larger budgets. Research has shown that national distribution of arts funding flows disproportionately to large institutions, which puts culturally specific organizations at a disadvantage (Sidford and Frasz 2017). Culturally specific organizations are affected by the same structural racism and inequities that affect the people and communities they serve.

What might the impact of COVID-19 look like for the 12-month period from March 2020 through February 2021 for the nation’s nonprofit arts and cultural organizations, assuming an October 1, 2020, reopening? While no one has a crystal ball or data on the future, we turn to historical financial, operating, and attendance data, and model estimates based on arts and cultural organizations’ reported COVID-19-related decisions and impact to date (see the Table below). While imperfect, these predictions help us to consider longer-term macro effects of the current crisis on the field while inviting conversations now about the deficit level the average organization can reasonably expect.

The estimated aggregate -$6.8 billion net effect of the COVID-19 crisis on the nonprofit arts and culture sector equates to a deficit equivalent to 26% of expenses for the average organization.

These estimates relate to activity for roughly 35,000 nonprofit organizations in the U.S. with annual budgets over $50,000 whose primary mission is arts and culture.[i] It under-represents the full universe of artistic and creative activity that Americans enjoy. The estimates incorporate what arts organizations have reported through surveys about closures, layoffs, and impact to date,[5] reinforced by qualitative insights;[6] survey results on audience intention to attend (Dilenschneider 2020b); and trends during and after the Great Recession (Voss, Lasaga and Eyring 2019).

They take into account variations across arts and cultural sectors related to expectations about impact and reopening, where sector-level data are available. We are grateful for the leadership and collegiality of Theatre Communications Group, Association of Art Museum Directors, Association of Performing Arts Professionals, the League of American Orchestras, Chamber Music America, The International Association of Blacks in Dance, and First Peoples Fund for sharing insights from their member surveys. These national service organizations have been working closely with their member organizations to support them in this time of crisis and gather data critical to understanding impact.

These estimates are built on the base scenario that the majority of organizations will be able to resume activity October 1, 2020. Some will open sooner, particularly those in parts of the country with lower incidences of the virus or those that allow for greater flexibility in the movement of people, such as museums (Dilenschneider 2020c). Many organizations with concentrated summer programs have already made the difficult decision to cancel them entirely, and some organizations have cancelled all programs through spring 2021.

Assumptions for this model are based on the most severe impact occurring in the first three months of March-May, 2020, with idiosyncratic slow recovery starting in the four months that follow as some organizations restart programming, experiment with alternate delivery channels,[7] and bring back furloughed employees in stages. The final stage assumes the bulk of organizations reopening October 1, 2020, with restrictions on the number of people allowed to gather. The estimates do take into account the strong likelihood of social scarring, and are based on slow, gradual resumption of attendance and participation as people start to feel that arts venues are places where they can safely gather.

There are specific steps that organizations can consider taking to address the current crisis and even to grow for the future. They reflect the three propositions that any organization can develop and align in order to achieve success: its value proposition, revenue proposition, and people proposition (Kim and Mauborgne 2009). Success requires a value proposition – a set of benefits exceeding costs – that are attractive to some set of individuals.

This is the utility that those served perceive about an offering that exceeds the price they are willing to pay for it, monetary or otherwise, or the utility those who support the organization see in its provision of services to a community. The revenue proposition (or “profit” proposition in a for-profit context) enables the organization to generate sustainable revenue out of the value proposition from some set of stakeholders. The people proposition must motivate and enable those working for or with the company to successfully carry out the value and revenue propositions.

What is the source of our strength? What do we do that is most meaningful and relevant to the community?

Not surprisingly, the first and most crucial step relates to mission. Like all nonprofits, arts and cultural organizations have well-articulated mission statements that describe why they exist and why their impact matters. Ideally, an organization will have internal alignment around a stated purpose that is meaningful to the community. As an arts leader suggested, “Figure out what aspects make your organization unique, and narrow that list to the aspects people care about.” This is the essence of an organization’s value proposition. How an organization carries out its purpose can vary over time as it innovates, and in response to changing community needs, to new opportunities, or to radical environmental shifts.

At this pandemic time, we encourage organizations to be clear about the service they provide to communities and ensure that their posture, via messaging and action, reinforces their service. We examined survey responses of arts organization leaders about the COVID-19 crisis. They revealed that many organizations are confronting hardships and their need is real and considerable. It is a natural instinct to ask for help in times of need.

Yet rather than focus messaging solely on what the organization needs in this moment in order to make a come-back, organizations might consider shifting their focus outward to their community’s needs. As Steven Nardizzi (2020) observes, “Your donors aren’t giving to your organization.

They’re giving through your organization to a cause they care about. Your mission and impact are what resonate with your donors. It’s what brought them to you in the first place.” An organization that seeks to be relevant challenges itself to be part of solving needs in potentially new and creative ways (even if the articulated need is “distraction from stress,” which is entirely legitimate at this time). Keeping mission-centric service to the community first, when the very confines of community are changing, will inevitably shift arts organizations’ program, communications and content distribution strategies.

Changes in the environment are forcing organizations to adapt and be innovative in how they provide value to their communities.

What do you have? What do you do? What do you know? How can you leverage these assets to better the lives of people in your community?

There is news from the field about the myriad ways in which arts organizations have served their communities and lifted spirits in this time of crisis. Organizations of every size and sector in markets across the country are building engagement through innovative online programming (Americans for the Arts 2020; Gaskin 2020).

There are audio seasons, education programs, tours, video series, concerts performed by artists from their homes, and new Zoom productions. Costume shops sew protective masks. Singing telegrams by opera singers lighten the days of health care workers and those who are infirm or isolated. Partnerships have emerged that engage artists and arts organizations in the creation of murals at hand-washing stations.

The arts and creative expression have provided a critical way to connect and reduce stress. While expensive given the current state of technology, there is potential in new forms of digital connection that are just starting to emerge such as augmented and virtual reality, and artificial intelligence. On the other end of the technology spectrum, some organizations recognize that not every household has internet access, so they are mailing resources such as workbooks to low income participants in education programming. This time of crisis begs arts and culture organizations to leverage this moment in ways large and small for mission-driven evolution.

How will we manage our people and revenue propositions to confront the new reality?

The human tragedy and financial stress of the current moment can feel paralyzing. And yet, this is a time when arts leaders and board members would benefit from contemplation of the longer term, while still figuring out how to survive in the short term. Based on our estimates, the months to come are likely to leave the average organization with a 12-month deficit equivalent to 26% of its budget.

Each organization can create its own estimates for the future. That exercise can be accompanied by discussion among artists, staff and board members of the roadmap for how the organization will emerge, over time, to a place of financial stability.For some organizations, the most secure road to the future will result in planned, sustained closures until later in 2021[8] and for others it is resulting in testing the return much sooner.[9]

In and of itself, the act of creating a grounded action plan to attaining or retaining financial stability feeds optimism. Passion resides within the people who deliver mission-related work as well as the individuals who support and are served by that work.

With leaner staffs and resources, organizational leaders will want to consider ways to collectively galvanize talents and open communication. That means de-siloing teams (Tett 2015) and working to focus on today’s required results, rather than solely pre-COVID department priorities. For example, one arts leader reported artistic production staff lending time to making subscriber and donor calls; another reported finding copy-writing talent in the box office and applying those skills to the increased needs for audience communications.

Daily huddles and weekly team pacing meetings now take place at nimble organizations, sometimes with the entire remaining artistic and administrative team, focused on weekly and daily operational and strategic goals. Boards are deeply engaged as well. Greater collaboration and transparency have the residual benefit of developing trust, team support, and culture during the most stressful of times. This can be especially important as remaining staff members may be coping with trauma in their personal lives and anxiety about continued job security should another wave of the virus emerge.

Likewise, audience development, segmentation of audiences and individual donors, and community outreach are more important than ever during this crisis. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations widely developed broad digital outreach and content distribution schemes. These efforts continue to allow organizations to serve the broader public free of charge in meaningful ways, as illustrated above.

Now organizations are complementing these efforts by mobilizing to create segmented, curated patron offerings and communication that can help stabilize a base of financial support that will serve as a foundation for future audience and donor expansion.[10] Strategies being tested include gated performance access, digitally offered education programs (complete with paid and unpaid enrollment), and curated content with artists available only to donors/members/subscribers.

TRG Arts is currently collecting and analyzing live purchase and individual contribution data from hundreds of organizations free of charge, which is feeding real-time intelligence on consumer behavior and actionable insights. Data collected and shared through its free COVID-19 Benchmark[11] reveals that loyal patrons – i.e., those who have purchased or donated at least three times with an organization, the latest of which was in the past 18 months – are fueling future investment in the arts and cultural sector. TRG is now working to provide tools and resources to support that necessary relationship management and content/program development planning.

A bigger challenge on a volume basis is engaging those who were infrequent and lapsed audience members pre-COVID. To address this, organizations are testing “futures” programs that enable the community to invest in the future of an arts or cultural organization, regardless of the anticipated date of reopening, by purchasing either tickets or credit now for future programming. Subscription and membership programs can evolve to this “futures” model should dates move further into the future (Robinson 2020a). Philanthropic giving, a considerable driver in current revenue streams, reflects a similar investment.

When our doors reopen, whom will we gather?

The broader and equally important challenge relates to community relevance. The local community in which an organization operates will be essential to the sector’s recovery, for mission-related and practical reasons. The desire to socialize is a primary motivator of live arts attendance (National Endowment for the Arts 2015).

Ultimately, the communal nature of arts participation will be a strength to communities hungry to come together again and affirm existential meaning after prolonged isolation. On a practical level, myriad research studies regarding consumer confidence put travel at the bottom of the recovery, suggesting that local audiences, local talent, indeed, the local supply chain will reign supreme.[12]

This is a watershed moment for arts and cultural organizations. The crisis has laid bare racial and income divides in society, intensifying pre-crisis inequity and polarization that were already in a heightened state. COVID-19’s toll on lives and well-being has affected everyone, but people of color and low-income individuals have suffered disproportionately (Evelyn 2020; Sánchez-Páramo 2020).

Reopening will be an opportunity to send a signal about the role the organization wants to play in the local community moving forward. It represents an opportunity to be part of the solution to healing divided communities at a critical time. Shared cultural experiences attenuate negative perceptions of others, unite spatially and socially divided citizens, and facilitate access to a better quality of life for everyone in the community (UNESCO 2001). Research has shown that arts attendance brings positive social spillover effects. For instance, those who attend the arts are more than three times as likely to volunteer as non-attenders (Nichols 2007).

Resilient organizations will be those whose work is meaningful to a sufficiently large segment of the local community that cares whether they exist. Culturally specific organizations have devoted their existence to serving diverse segments of the community, and equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) goals related to audiences and the workforce have been increasingly pursued by arts organizations[13] and supported by funders over recent years (Grantmakers in the Arts 2019).

Short-term survival instincts will no doubt surface, as reflected in this comment recently expressed by an arts leader: “Our concern coming out of this crisis will be that we need to focus on revenue-driven projects (since we’re all facing so much financial loss right now) and important EDI missions will be put on hold.” We argue that arts and cultural organizations have an opportunity to take a leadership role in communities by keeping EDI within their sphere of focus in creating revenue-driven projects.

When organizations provide programming that makes them relevant to only a small slice of the community, they not only expose themselves to risk when that narrow slice diminishes in size with shifting demographics (e.g., Frey 2018), but they also miss opportunities to increase their footprint of relevance. If we leave others behind, we will ultimately be left behind. To quote business strategist Fred Reichheld, “What you do now—how you treat your patrons and employees—will be what everyone remembers after the COVID-19 crisis recedes.”[14]

Might moves to digital forums and nimble distribution channels help organizations to better navigate some of these changes? For example, research shows that arts attendance begins to decline around age 72 (DeGood and Tulepkaliev 2019). Within 10 years, the boomer generation will be solidly in this declining age demographic. Might digital distribution of arts and culture content help us continue meaningful relationships in the lives of an aging population, enabling them to participate longer? Could newly expanding digital offerings also reach into a younger demographic that is more racially diverse and technically savvy than older generations, and will become increasingly so?[15]

How can decisions made today improve sustainability for the long haul?

Arts and cultural leaders have an opportunity to learn from this experience and to plan and imagine differently than ever before (Robinson 2020b; AMS Planning and Research 2020). The big-picture strategic questions explored in this paper are among a myriad of variables that have to be carefully considered, such as continued presence and relevance while closed, timing of reopening and implications for artists and staff,[16] creation of a safe but profound reentry experience for the community, realistic expectations about gradual resumption of attendance and participation, business model changes, and programming decisions.

In the interest of long-term resiliency, organizational leaders and board members may want to begin conversations now for how they will recover from a deficit if their projections align with estimates provided here, and whether working capital reserves will become an essential part of financial planning moving forward. Scenario planning can help organizations to think through the path that is right for them given their circumstances.[17] Data must be reviewed weekly to assess which scenario is being realized, and free tools, research, and resources such as those provided by TRG, SMU DataArts, and others can be used along the way.

ABOUT SMU DATAARTS

SMU DataArts, the National Center for Arts Research, is a joint project of the Meadows School of the Arts and Cox School of Business at Southern Methodist University. SMU DataArts compiles and analyzes data on arts organizations and their communities nationwide and develops reports on important issues in arts management and patronage. Its findings are available free of charge to arts leaders, funders, policymakers, researchers and the general public. The vision of SMU DataArts is to build a national culture of data-driven decision-making for those who want to see the arts and culture sector thrive. Its mission is to empower arts and cultural leaders with high-quality data and evidence-based resources and insights that help them to overcome challenges and increase impact. To work toward these goals, SMU DataArts integrates data from its Cultural Data Profile, its partner TRG Arts, and other national and government sources such as Theatre Communications Group, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Census Bureau, and IRS 990s. Publications include white papers on culturally specific arts organizations, the egalitarian nature of the arts in America, gender equity in art museum directorships, and more. SMU DataArts also publishes reports on the health of the U.S. arts and cultural sector and the annual Arts Vibrancy Index, which highlights the 40 most arts-vibrant communities around the country. For more information, visit www.culturaldata.org.

ABOUT TRG ARTS

The Results Group for the Arts (TRG Arts) is a data-driven management consulting firm that teaches arts and cultural professionals a patron-based approach to increasing sustainable revenue and provides aggregated arts consumer analytics and research tools to global communities and policy makers. Since its founding in 1995, nonprofit and commercial entertainment partner clients of TRG Arts have achieved results positively affecting organizational revenue models and consumer loyalty. TRG Arts believes in the transformative power of arts and culture, and that positive and profound change in the business model of arts organizations can lead to artistic innovation and the ability to better inspire entire communities.

REFERENCES

[1] The authors wish to acknowledge the following colleagues for their helpful comments, suggestions, and insights: Heather Kim, Director of Institutional Research, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Sunil Iyengar, Director for the Office of Research and Analysis, National Endowment for the Arts; Randy Cohen, Vice President of Research and Policy, Americans for the Arts; Daniel Fonner, Associate Director of Research, SMU DataArts; Anita Hansen, Senior Consultant, TRG Arts.

[2] Quoted in Burke, Siobhan (2020), “This Artist Proposes a Community Space ‘to Dream, to Imagine’” The New York Times, 15 April, retrieved 19 April 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/arts/dance/jaamil-olawale-kosoko-chameleon.html.

[3] https://aeaconsulting.com/insights/thank_you_for_the_opportunity

[4] See https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/why-are-so-many-black-owned-small-businesses-shut-out-n1195291.

[5] The authors are grateful for The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s help facilitating contact with national service organizations for access to member surveys.

[6] Of the nearly 150 multi-genre chief executives in consulting relationships with TRG Arts or attending its virtual Executive Recovery Summits as of this writing, 100% report negative effects on all three variables mentioned above—staff levels (including artistic), event schedules and expected 2020 financial results. TRG continues to host twice-weekly Recovery Summits as the crisis unfolds.

[7] See https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2020/04/performing-arts-in-the-covid-19-shutdown

[8] See https://www.americantheatre.org/2020/05/09/guthrie-to-stay-closed-until-march-2021-mini-season/

[9] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/28/theater/barrington-stage-coronavirus.html

[10] An example: https://www.broadwayworld.com/washington-dc/article/BWW-InterviewJennifer-Buzzell-and-James-Gardiner-of-Signature-Theatre-Talk-Keeping-the-Company-Vital-Without-a-Live-Audience-20200508

[11] For more information or to enroll, see https://www.trgarts.com/Whatwedo/AnalyticsResearch.aspx

[12] See, for example https://morningconsult.com/2020/04/10/consumer-expectations-normal-activities-comfortable/

[13] See, for example, League of American Orchestras (https://americanorchestras.org/learning-leadership-development/diversity-resource-center.html), American Alliance of Museums (https://www.aam-us.org/category/diversity-equity-inclusion-accessibility/), Theatre Communications Group (https://www.tcg.org/EDI/Overview.aspx).

[14] https://www.trgarts.com/Whoweare/PressandMedia.aspx

[15] https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

[16] See, for example, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/04/a-r-t-and-chan-school-building-a-healthy-roadmap-for-theater/

[17] See, for example, https://www.trgarts.com/Whatwedo/AnalyticsResearch.aspx

[i] The estimates of 12-month activity are drawn primarily from 2018 IRS 990 forms, which were filed by tax-exempt organizations with budgets of $50,000 or more. Estimates for employees, contracted workers, and total attendance were derived from data from DataArts’ Cultural Data Profile (CDP) and Theatre Communications Group (TCG). IRS data also includes a line item for number of employees, but reporting is sparse.

The organizations included in the estimates are all classified as A-Category in the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE), a classification system to identify nonprofit organization types. “Arts and Culture” is one of the NTEE’s 10 major groups of tax-exempt organizations (the “A” category), and within Arts and Culture there are 10 subcategories that contain 30 additional subdivisions.

The estimates are informed by survey data collected by national service organizations about their members’ current and projected COVID-19 impact on revenue, expenses, employment, and cancellations. Since survey results revealed marked differences in earned revenue and attendance loss attributable to cancelled programming, we vary the attendance and program revenue estimates by arts and cultural sector. There was reasonable similarity across survey results for arts sectors in current and projected changes to employment, contributed revenue, and other revenue (e.g., rentals, investment instrument income, etc.).

Numerous surveys asked participants to report the percentage that losses in each category represent over a set time frame (e.g., What percentage of your total budgeted ticket revenue for your current fiscal year do you estimate will be lost because of COVID-19?). In these cases, we calculated the median and mean for each item. Where the two were similar, we applied the mean percentage loss per category to the total annual average from the IRS data, prorated for the number of months reflected in the time period in question. We then estimated future losses on a diminishing scale (i.e., slowly improving over time), assuming an October 1 opening for performing arts and arts education organizations and a June 1 opening for museums and community-based organizations.

This scale takes into account current purchase behavior, research on intent to visit (https://www.colleendilen.com/category/covid-19-updates/), and estimates provided by several of the national service organizations. Where the mean was skewed by a subset of outliers, we split the respondents into two groups around the median, and used the mean of the two groups in proportion to the number of organizations they represented. While the resulting estimate did not change drastically from what we would calculate using the mean of respondents as a whole, we felt it important to make a best effort to capture the story of organizations disproportionally affected. Please direct questions to the first author.

Americans for the Arts (2020), “The Economic Impact of Coronavirus on the Arts and Culture Sector,” May, Retrieved from https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-topic/disaster-preparedness/the-economic-impact-of-coronavirus-on-the-arts-and-culture-sector.

AMS Planning and Research (2020), The Long Runway to Return: The Role of Anchor Cultural

Institutions, April, Retrieved from https://www.ams-online.com/long-runway/.

Bruch, Heike and Sumantra Ghoshal (2003), “Unleashing Organizational Energy,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Fall, 45 (1), 45-51.

DeGood, Jim and Nariman Tulepkaliev (2010), “Generational Analysis 2019,” TRG Arts, Retrieved from https://trgarts.com/TRGInsights/Article/tabid/147/ArticleId/527/Generational_Analysis_2019.aspx.

Dilenschneider, Colleen (2020a), “Performance vs. Exhibit-Based Experiences: What Will Make People Feel Safe Visiting Again?” Know Your Own Bone, April 15. Retrieved from https://www.colleendilen.com/2020/04/15/performance-vs-exhibit-based-experiences-what-will-make-people-feel-safe-visiting-again-data/.

Dilenschneider, Colleen (2020b), “How COVID-19 is Impacting Intentions to Visit Cultural Entitites,” Know Your Own Bone, April 27. Retrieved from https://www.colleendilen.com/2020/04/27/data-update-how-covid-19-is-impacting-intentions-to-visit-cultural-entities-april-27-2020/

Dilenschneider, Colleen (2020c), “Which Cultural Entities Will People Return to After Reopening?” Know Your Own Bone, April 22. Retrieved from https://www.colleendilen.com/2020/04/22/data-update-which-cultural-entities-will-people-return-to-after-reopening-april-22-2020/.

Evelyn, Kenya (2020), “'It's a racial justice issue': Black Americans are dying in greater numbers from Covid-19,” The Guardian Weekly, April 8, Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/08/its-a-racial-justice-issue-black-americans-are-dying-in-greater-numbers-from-covid-19.

Frank, Hermann, Wolfgang Güttel, Alexander Kessler (2017), “Environmental dynamism, hostility, and dynamic capabilities in medium-sized enterprises,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 18 (3), 185-194.

Frey, William H. (2018, June 22), “US White population declines and Generation ‘Z-Plus’ is minority White, census shows,” Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/06/21/us-white-population-declines-and-generation-z-plus-is-minority-white-census-shows/.

Gaskin, Sam (2020), “Google Arts & Culture Booms as Art World Moves Online,” Ocula, March 30. Retrieved from https://ocula.com/magazine/art-news/interest-in-google-arts-culture-skyrockets-as/.

Gopinath, Gita (2020), “The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression, International Monetary Fund,” April 14. Retrieved from https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/.

Kim, W. Chan, and Renée Mauborgne (2009), “How Strategy Shapes Structure,” Harvard Business Review, September, 87 (9), 72-80.

Nardizzi, Steven (2020), “In Times of Crisis, Don’t Create Your Own,” The NonProfit Times, April 28. Retrieved from https://www.thenonprofittimes.com/fundraising/in-times-of-crisis-dont-create-your-own/?utm_source=Full+NPT+Active&utm_campaign=40844cac49EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_05_14_02_27_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_639f32315240844cac4996830995&mc_cid=40844cac49&mc_eid=ca1ea9e9ba.

National Endowment for the Arts (2020), The U.S. Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account, Arts Data Profile #24. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/artistic-fields/research-analysis/arts-data-profiles/arts-data-profile-24.

National Endowment for the Arts (2015), When Going Gets Tough: Barriers and Motivations Affecting Arts Attendance, NEA Research Report #59, January. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/publications/when-going-gets-tough-barriers-and-motivations-affecting-arts-attendance.

Nichols, Bonnie (2007), Volunteering and Performing Arts Attendance: More Evidence for the SPPA, NEA Research Report #94, March. Retrieved from https://www.arts.gov/publications/volunteering-and-performing-arts-attendance-more-evidence-sppa.

Robinson, Jill (2020a), “Investing in Futures in the Arts,” TRG Arts, April 3, Retrieved from https://trgarts.com/TRGInsights/Article/tabid/147/ArticleId/595/Inspiring-Futures-in-the-Arts.aspx.

Robinson, Jill (2020b), “Planning for Pivots,” TRG Arts, April 10, Retrieved from https://trgarts.com/TRGInsights/Article/tabid/147/ArticleId/597/Planning-for-Pivots.aspx.

Sánchez-Páramo, Carolina (2020), “COVID-19 Will Hit the Poor Hardest. Here’s What We Can Do About It,” World Bank, April 23, Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/covid-19-will-hit-poor-hardest-heres-what-we-can-do-about-it.

Sidford, Holly and Alexis Frasz (2017), Not Just Money: Equity Issues in Cultural Philanthropy, Helicon Collaborative, July, retrieved from http://www.notjustmoney.us/docs/NotJustMoney_Full_Report_July2017.pdf.

Sneader, Kevin and Shubham Singhal (2020), Beyond Coronavirus: The Path to the Next Normal, McKinsey and Company, March.

Tett, Gillian (2015), The Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Thomas, Rebecca and Zannie Voss (2018), Five Steps to Healthier Working Capital, SMU DataArts, Retrieved from https://dataarts.smu.edu/artsresearch2014/working-capital.

Voss, Zannie, Manuel Lasaga, and Teresa Eyring (2019), Theatres at the Crossroads: Overcoming Downtrends & Protecting Your Organization Through Future Downturns, SMU DataArts, Retrieved from https://culturaldata.org/pages/theatres-at-the-crossroads/.

Voss, Zannie, Glenn Voss, Andrea Louie, Zenetta Drew, Marla Teyolia (2016), Does ‘Strong and Effective’ Look Different for Culturally-specific Organizations? SMU National Center for Arts Research. Retrieved from https://dataarts.smu.edu/artsresearch2014/NCARDiversityPaper.