Five Steps to Healthier Working Capital

By Rebecca Thomas, Principal, Rebecca Thomas & Associates and Zannie Voss, NCAR Director

Has your organization ever been cash-strapped? If so, you know more than you may want to know about the importance of working capital. While few arts leaders wake up with excitement over working capital management, many lose sleep over it.

They should. NCAR’s analysis shows that working capital hovers at precariously low levels for the majority of cultural organizations. For example, the overall average working capital for performing arts organizations, as well as for half of the museums, is fewer than two months. Moreover, working capital has decreased over the last three years.

In this paper we will address why liquidity matters, share findings on the working capital levels of arts and cultural organizations, and provide five steps to healthier working capital through savings strategies.

Why does liquidity matter?

A sustainable cultural organization has the financial resources to support its mission over the long term. It raises and earns enough revenue to cover its full costs each year, and it has adequate flexible cash (or other short-term assets) on hand or readily available.

Working capital is a simple calculation of unrestricted current assets minus current liabilities. When organizations have sufficient working capital, they can manage and take risks. They have enough cash to cover short-term obligations to others, such as banks, vendors, or employees. They navigate unpredictable shortfalls in revenue, perhaps due to the loss of a funder, leadership transition, or economic downturn. They fix, improve, or replace facility systems, technology, and equipment. And, they experiment artistically in ways that might not otherwise be affordable.

Healthy working capital gives arts leaders breathing room. Faced with uncertainty, or the prospect of loss, organizations with adequate savings can reflect on, and reconsider, the best path forward, knowing that a deficit won’t put them out of business.

Working Capital: The story in the numbers

In 2016, the average arts and cultural organization had working capital equivalent to 5 months’ worth of total expenses.[1] While this might seem like a comfortable cushion, it reflects very high levels of working capital concentrated among a minority of institutions. Many segments of the field had far less working capital. Moreover, the majority of organizations experienced a decline over time: 55% of organizations had less working capital relative to their expenses in 2016 than in 2013.

How did months of liquidity end up lower? The multi-year decline reflects two trends. First, growth in unrestricted current assets did not keep up with growth in current liabilities. Second, expenses steadily increased for the average organization, reducing the value of existing liquidity.

Museums fare better than Performing Arts

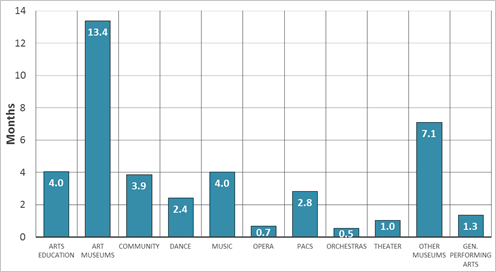

Average working capital levels vary widely across arts and cultural sectors as shown in Figure 1. Museums averaged far higher levels of working capital than other types of arts and cultural organizations and skewed the overall average high, a phenomenon that was true not only for 2016 but also for the 3 years leading up to it. As Jeremy Strick, director of the Nasher Sculpture Center, explained,

“[We] have high fixed costs, and program costs can not only be high, but they can be lumpy. That is, since much of the expense for a given exhibition can fall within a limited time, and the flow of earned income and membership income is fairly steady, it can be helpful to have a larger pool of working capital.”

As we dug deeper, we found that some museums exerted a particularly dominating influence on working capital. To better reflect the overall museum experience, we looked at the median (i.e., midpoint in the range) level of working capital. Here, a more sobering figure emerged: the median art museum’s 2016 working capital was only 1.5 months, compared to 13.4 months for art museums on average.

Performing arts sectors broadly exhibited a more precarious liquidity position: they held from 2 weeks to 4 months of working capital and collectively averaged just 1.7 months’ worth. Operas, theatres, and orchestras averaged one month of liquidity or less.

Figure 1: 2016 Average Months of Working Capital, by Sector

The deterioration in liquidity over time is widespread across artistic disciplines. The average organization in every sector except Music experienced more constrained working capital in 2016 than in 2013. The growth in working capital in the Music sector tracks with that sector’s consistent achievement of annual surpluses.

Small groups fare better than medium and large ones

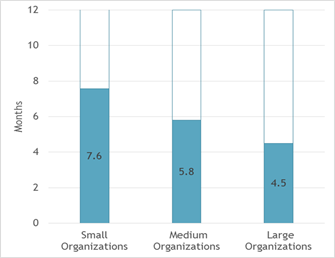

Examining working capital by budget size rather than sector, we found that small organizations had more liquidity relative to expenses, on average, than their medium and large peers in 2016, as shown in Figure 2.[2]

Figure 2: 2016 Average Months of Working Capital, by Size

Further, the data shows that 2016 capped off a four-year period during which small organizations increased their working capital, mid-sized organizations maintained their liquidity, and large-budget organizations experienced erosion in working capital levels.

The majority of small organizations grew their working capital through healthy surpluses over the period. As highlighted in NCAR’s Bottom Line Report, these organizations have lower fixed costs and therefore tend to be more nimble than their larger peers. More than half (53%) of small organizations that reported balance sheet data experienced growth in their operating surplus over time, and two-thirds of these organizations also grew total unrestricted net assets.

We conclude that smaller organizations did not use their surplus cash for facility or equipment expansion, a strategy that often increases business risk. In fact, only 4% of these organizations experienced growth in net fixed assets, while 52% reported no change, and 44% experienced declines. Declining fixed asset balances could be a sign that smaller groups feel they need to conserve cash at the expense of replacing depreciating space improvements, equipment, or technology.

In contrast, in large organizations, deficits caused working capital to decrease. These deficits corresponded with expense growth averaging 4% over the period. While larger groups still had some cash to sustain themselves during this period, they are steadily draining their well of savings. If the downward trajectory continues, large organizations will face tough times ahead.

Finally, medium-budget organizations fared well by staying the course. They kept a lid on expense growth and experienced minimal fluctuation in bottom line results, which hovered just above or below break-even. As a result, months of working capital for this group remained stable between 2016 and 2013.

This data is instructive. When organizations grow, often by adding new permanent costs and infrastructure, their financial health frequently suffers. Increasingly, perhaps, small- and medium-budget organizations are finding a sweet spot: many have reached a point in their growth trajectory where they can more predictably live within their means and hold onto enough cash for comfort.

What can be done to build savings?

Nonprofits show leadership by taking sustained action to accumulate and maintain adequate savings. Grantmakers and donors increasingly put a premium on strong financial management. They expect organizations to act more as businesses, always for the ultimate sake of mission. Grantmakers in the Arts (GIA), the national association of public and private arts and cultural funders, has led a sustained effort to educate and influence institutional grantmakers on the importance of encouraging and incentivizing surpluses and savings. Many foundations are changing their due diligence and grantmaking practices in response.

Cultural organizations can capitalize on this moment by putting in place the discipline and practices that help ensure financial health for a long time to come. We offer the following recommendations:

-

Set savings goals as part of long-term planning

Financial goal-setting is often perceived as the ugly stepchild of strategic planning. Cultural leaders, many of whom have never been trained in nonprofit finance, can be uncomfortable translating their artistic strategies into business assumptions with financial targets. Cultural leaders can mitigate strategic risks by integrating financial planning into their strategy development process. This work starts with setting appropriate financial goals:

- How much working capital should we have on hand to ensure the timely payment of bills during slower months of revenue receipt?

- How much unrestricted cash do we strive to place in reserve to manage an unexpected revenue shortfall?

- Should reserve funds be set aside to help address the annual or periodic wear and tear on a facility or other fixed assets?

- What artistic opportunities on the horizon might require upfront infusions of cash before a potential financial return?

The next step is to develop a financial roadmap that plots out how, and over what timeframe, the organization plans to achieve its savings goals. Remember, every organization has a different set of balance sheet priorities and will follow a different path to meet them.

(For more on this topic, see 6 Steps to Sustainability Planning)

-

Plan for – and manage to – surpluses

Organizations primarily build working capital through the generation and set aside of surpluses. When arts leaders budget to the zero mark – often because they are encouraged to do so by board members or some funders – they unintentionally perpetuate a starvation cycle. They spend every last dollar of revenue raised or earned, making it impossible to create short- or long-term savings.

As part of the annual budgeting process, cultural leaders should set surplus targets that connect to their savings goals. For example, if an organization strives to secure three months of working capital over three years, its budget should plan for annual surpluses equivalent to one month’s expenses. Boards of directors and staff need to monitor progress toward surplus goals. If revenue starts falling short of goal, or expenses run materially ahead of plan, it’s time to consider action to bring revenue and expenses back into alignment.

Even in financially disciplined organizations, deficits happen from time to time. Predicting the loss of an important supporter, the departure of a critical staff person, or the onset of economic retrenchment is quite difficult. Still, cultural leaders need to be prepared to respond quickly, by doubling down on strategies to deepen relationships with audiences and patrons – or sometimes, by making tough decisions to do less, while returning their organization to predictable surplus performance.

-

Explore special fundraising for reserves

Many cultural organizations find it impossible to achieve their comprehensive savings goals through surpluses alone. They may start or grow savings in reserve by making a special fundraising request, or expanding the goals of a capital campaign. Organizations should examine their donor relationships and ask:

- Which supporters might seed the creation of, or grow an existing, cash reserve for risk-management or periodic risk-taking?

- Can a request for reserve funding be structured as a matching opportunity?

- Does an upcoming or envisioned capital campaign present an opportunity to raise cash for facility preservation and stewardship, in addition to new bricks and mortar?

- What role can the board play in kick-starting efforts to build one or more reserves?

When making a request for savings, organizations should lead with mission, answering: What will having more cash allow us to accomplish? Funders give to artistic potential and outcomes, not to balance sheets. So make the connection.

-

Set policies governing the use and replenishment of savings

Policies governing the use and expenditure of savings make it clear to all stakeholders – staff, board members, and supporters – that an organization has considered the responsible use of its hard-earned assets. As a communications tool, cash reserve policies can help dispel any notion that an organization is “hoarding” its cash.

These policies clarify the purpose of cash held in reserve, specify who can approve drawdowns of a fund, and clarify the reasonable timeframe in which approved cash expenditures will be replenished.

While it can be tempting for boards of directors to “bottle up” all working capital, we encourage them to resist this temptation. Some operating capital, usually a few or several months’ worth, should always be readily available for use at management’s discretion for the timely payment of bills.

-

Build assets in the right order: Unrestricted liquidity comes first

This paper focuses on unrestricted working capital. Many cultural organizations hold additional longer term, fixed and/or restricted assets. In some cases, these assets bring added stability. For example, a museum may benefit from using the income from an endowment to help care for its collections. However, in building restricted or fixed assets, many cultural organizations unintentionally erode or neglect working capital. This is something to watch out for. Some examples:

- Endowments: In pursuit of permanently restricted assets, cultural organizations can become distracted from raising flexible annual funds for operations. Financial performance and working capital levels, both suffer. Endowments are a source of revenue, not liquidity. They can’t be used for cash flow management, or as a cushion against risk.

- Fixed assets: During and after facility expansion or improvement projects, cultural groups frequently experience significant declines in working capital levels. Project cost overruns are common. Transition costs are frequently underestimated. Operating deficits occur more often than not when program or staff growth accompanies the move to a larger space.

- Temporarily restricted assets: Typically, these grants fall short of covering the full costs of their intended program or project. This can make it harder for organizations to achieve the surpluses that support working capital creation.

Some of these impacts are outside of organizational control. Others are not. Regardless, short-term unrestricted liquidity should always come first.

In closing, organizational leaders needn’t be daunted by the journey to stronger financial health.Building liquidity and reserves doesn’t happen overnight. Even if it did, capital needs change from one year to the next. Just as organizations continuously revisit and refresh their artistic plans, so must they regularly re-establish balance sheet goals.The journey may never end, but the artistic sights along the way should make the trip worthwhile.

[1] Findings reported in this paper are from the National Center for Arts Research’s Working Capital Report, which can be found at www.smu.edu/artsresearch.

[2] For further detail and to see budget size cut-off points by arts and cultural sector, visit: www.smu.edu/artsresearch