- Sector Scan

Data, Diversity, and The Information Age

- Posted Jan 28, 2021

There's no doubt that the events of last year have forced many of us to reflect on the systems in which our cultural organizations operate and the patterns that limit progress toward racial equity. Gary Anderson of Plowshares Theatre Company shares his thoughts on why a re-evaluation of equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives and the data collection processes used to measure their success are now crucial.

As we have watched a transfer of power in Washington, shepherding in a new chapter for this country, we are aware of how much the last four years have been a war between the truth and lies. This battle against misinformation was one of the subjects covered in President Biden’s inaugural address. Advocating for a fierce adherence to truth and the accuracy of facts was his remedy for our divided nation. It shouldn’t be a debatable thing. But, yet, it is.

We have no better example of the problem as Biden described it than the recent attempt by former Census Bureau Director Steven Dillingham to rush out an incomplete data report on non-citizens. We know what that would have meant. It had the potential to deliberately disenfranchise millions of U.S. residents and the cities and states wherein they reside. Critical funds needed to sustain the nation’s population during a raging pandemic would have been denied, leading to scarcity of resources and the creation of a vulnerable segment of the population.

Needless to say, counting accurately is important. That is what the census is designed to do. An accurate accounting in the census has always been of importance to communities of color, particularly when it pertains to African Americans.

In 1787, delegates from the Northern and the Southern states hammered out a compromise at the Constitutional Convention to count three-fifths of the enslaved population for determining direct taxation and representation in the House of Representatives. Representation that rendered benefits to the slaveowners, but not to the enslaved.

Why all of this discussion of the U.S. Census in a blog post about cultural data collection? Because we live during “The Information Age,” yet in many ways, when it comes to capturing distinct information about African Americans, Latinx, Asian or Indigenous peoples, specifically at a time when the arts field has been called to do better, we don’t show very much interest in it. In many cases, data captured within the arts and cultural sector is rarely distilled through the prism of ethnicity. When the data is captured it is staggering just how much employment opportunities favor whites over every other ethnic group. This undermines our ability of anyone talking about progress with diversity.

So across the various disciplines, we can’t really tell if anything has changed. The call for racial justice that began last spring demands we measure good intention against actual results. Thus far, those results have been lacking.

Since the 1980s, certain hiring policies have been devised in order to address these demographic shifts. Such ambitious programming actions as non-traditional or color-blind casting – casting a woman and/or a person of color in a role traditionally written to be played by a white male – were advocated by Actors’ Equity Association (AEA) and others to address inequities in hiring. In spite of such efforts, employment statistics have shown little to no change. According to Richard Florida, almost three-quarters (73.8%) of all creative class jobs nationwide are held by white (non-Hispanic) workers, compared to about 9% (8.5%) by African Americans.

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion policies have been prescribed to improve these hiring statistics for artists of color. Similar policies reportedly have been designed to tackle diversity of audience and board membership within our better-funded institutions. Yet, in spite of millions of dollars awarded to these efforts, they have failed to move the needle.

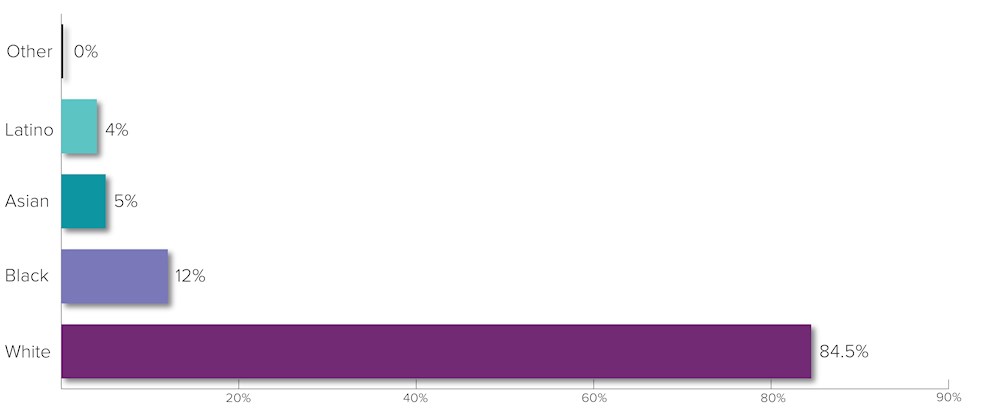

A report conducted by the Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC) that tracks the racial demographic data for Broadway and Off-Broadway casting since 2011 showed that white actors are hired eight times more often than Black actors on and off Broadway. At the conclusion of the 2014-15 season, the season “Hamilton” premiered on Broadway, the numbers were as follows:

Demographics of Actors Hired in Broadway Plays, 2014-15

This chart was originally presented in Black Theatre Survey 2016-2017, a report on the conditions affecting the long-term sustainability of Black Theatre.

In June 2017, AEA released the findings of their diversity study that analyzed the makeup of actors and stage managers nationally from 2013 to 2015. It found that white men made up the majority of all acting and stage management contracts, out of 63,603 contracts. In addition, women regularly commanded lower salaries than men. The racial breakdown for principal actors was as follows: Caucasians at 67%, African Americans at 9%, Latinos or Hispanics at 2% and Asians at 2%. The 20% balance either chose “other” or declined to identify their ethnicity. For principal roles in musicals, Caucasians held 71%, African Americans had 8%, Latinos or Hispanics had 2% and Asians had 2%. Again, the balance declined to choose to identify. There are even fewer people of color in stage management positions, with Caucasians at 74%, African Americans at 2%, Latinos or Hispanics at 3% and Asians at 1%.

These numbers are embarrassing for a nation that claims to serve all of its citizens with equal opportunities. None of this can be tackled without a rigorous examination of the arts world’s hiring practices, audience diversification techniques and board recruitment strategies, coupled with a much-needed review of changes in philanthropy. Data could help formulate strategies to move us towards a far more equitable playing field. It’s doubtful we could be any worst.

This pandemic has provided us with a pause in operations. At the same time, artists of color have increased their demands. They are expecting a far more aggressive approach to equity and inclusion when we reopen our theaters at the end of this national pause. The desire to return to pre-COVID normalcy. This would be a perfect time for our data collection agencies to better prepare the arts world to measure real progress. It’s the only way we can avoid finding ourselves frustratingly fighting the same battles 20-30 years from now.

This article was written by Gary Anderson, Artistic Director of Plowshares Theatre Company. He has worked on world premieres and established plays for over 25 years.

CITATIONS:

Florida, Richard. "The Racial Divide in the Creative Economy." CityLab, The Atlantic Magazine. 9 May 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-05-09/the-racially-divided-creative-class. Accessed 27 January 2021.

Bandhu, Pun. Ethnic Representation on New York City Stages 2014-2015. Asian American Performers Action Coalition, 2016.

American Theatre Editors. "White Men Get Majority of U.S. Jobs, AEA Study Finds." American Theatre Magazine. 29 June 2017, https://www.americantheatre.org/2017/06/29/white-men-make-up-majority-of-u-s-actors-aea-study-finds/. Accessed 27 January 2021.