- DataArts News

Understanding the Economy | Four Major Reasons Why Nonprofits Should Prepare for An Economic Downturn

- Posted Nov 12, 2019

This article is written to expand on topics related to the U.S. economy in the recently released Theatres at the Crossroads: Overcoming Downtrends and Protecting Your Organization Through Future Downturns.

The Great Recession was the longest recession that America had seen since World War II, lasting a staggering 18 months. It began at the peak of a U.S. business cycle in December 2007 and ended at its trough in June 2009. Low working capital, shifts in audiences and changing consumption behavior, and inequitable employment practices heading into the recession may have influenced how well an individual nonprofit arts organization was able to respond to the economic decline. However, research can help us understand sector-wide trends from this period and inform organizational leaders how to prepare for the future.

This past June marked the 121st consecutive month of economic growth after the Great Recession, so why are experts raising concerns that America will soon face another period of economic turbulence? And what does this mean for nonprofit arts and cultural organizations?

There are many factors that contribute to an organization’s overall financial health. While some of these factors fall squarely within management’s control, it’s also important to look to trends in the broader economic environment. Cultural organizations operate amidst the same day-to-day realities as any business, so the highs and lows of the economy may impact their health, stability, and in some cases, even their survival.

The U.S. business cycle has four distinct phases: Expansion, Peak, Contraction, and Trough. During a period of expansion, like that we’ve seen for the last 10 years, the economy grows at a healthy pace of 2% to 3%. Once the economy tips over into a growth rate of more than 3%, inflation sends prices up and we enter a peak period – or what many in the stock market refer to as a state of “irrational exuberance.” A period of contraction is when economic growth slows but isn’t negative. Once the economy contracts, it enters a trough phase. The trough phase can signal a recession, which is defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research as “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.”

Based on a report published by the Urban Institute in 2014, overall closure rates for arts organizations increased from 2.9% in 2008 to 3.9% in 2012. Overall, a 3.9% rate of closure is among the lowest compared with other nonprofit sectors. “Environment and Animals” was the only other sector to maintain a closure rate of less than 4% during this time. However, from 2.9% to 3.9% is a full 1% increase, which is among the highest increase rates across all sectors, and in line with the rate of closures for health organizations in 2012.

Interestingly, the number of arts and cultural organizations that lowered their annual revenue to below $50,000 also increased at a relatively high rate. In other words, while the rate of closure remained low, many arts and cultural organizations may have found ways to cut costs, bringing in less revenue but staying afloat during the economic decline.

Currently, the U.S. economy is healthy. There is growth in household income, recent record-low interest rates as well as unemployment rates, and consumer demand is in good shape. Additionally, global economic growth has been better than expected, which is helping to boost investment in technology and in turn boost U.S. economic growth. Despite these positive trends, there are still significant risks on the horizon that could greatly affect the economy and therefore the health of arts and cultural organizations across the nation. Here are four areas of concern that nonprofit organizations should be aware of.

International Relations: Trade with China and the U.K.

China is the world’s largest exporter and the U.S. is the world’s largest importer. Both serve as major pillars for the global economy. Throughout the last 50 years, the general consensus within the U.S. was that “an open and prosperous China is in the U.S. interest.” But as China quickly grew to become the second largest economy by the end of the 2010s, U.S. concerns about fair trade practices grew stronger.

In an effort to reduce the U.S. trade deficit, promote domestic manufacturing, and limit the theft of intellectual property, President Donald Trump implemented sweeping tariffs on China in response to its alleged unfair trading practices in July of 2018. Since then, the U.S. has applied tariffs on approximately $550 billion worth of Chinese products. In turn, China set tariffs on approximately $185 billion worth of U.S. goods. Further escalation of the current trade conflict between the U.S. and China, the two dominant economies of the world, could have negative, long-term consequences for inflation and global economic growth.

While certain industries have been affected more directly than others, growth in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) appears to be slowing, which may continue into 2020 and 2021 as a result of the disputes with China. This could have consequences not only for global influence but also for long-term economic policies related to trade, technology, and productivity.

Eventually, the two nations may reach a trade deal that reflects the interests of both sides, but depending on how much longer the conflict continues, it could cause fluctuations in the stock market, depress business and consumer spending, and erode consumer confidence, driving the U.S. economy down.

Additionally, current conflicts in Europe may also have a significant impact on U.S. trade. If the United Kingdom is to exit the European Union with no deal in place by the new deadline of January 31, 2020, it could have direct implications for U.S. exports and global or international trade. American producers selling to the U.K. could suddenly face barriers. According to senior fellow at the Peterson Institute of International Economics, due to the likelihood of the pound decreasing significantly in value and U.S. goods becoming more expensive.

Inflation and Productivity: Data Projections

In early January 2019, The Wall Street Journal surveyed 73 economists for insight into what may influence another economic downturn. More than half of the economists surveyed expected a recession to start in 2020 and another 26.4% expected a recession in 2021. One cause of concern was the possibility of a quickly rising rate of inflation; the article stated that “some economists cited the risk that rising inflation could lead to a faster pace of interest-rate increases by the Federal Reserve.”

Inflation is the percentage increase in the prices of goods and services over time. Recent inflation trends are driven by oil prices, unemployment, productivity and unit labor costs (ULC), capacity utilization, and tariffs. Tracking and analyzing inflation is critical because it is one of the essential measures the Fed uses in decision-making to fulfill its mandate from Congress, which is to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates in the U.S. economy.

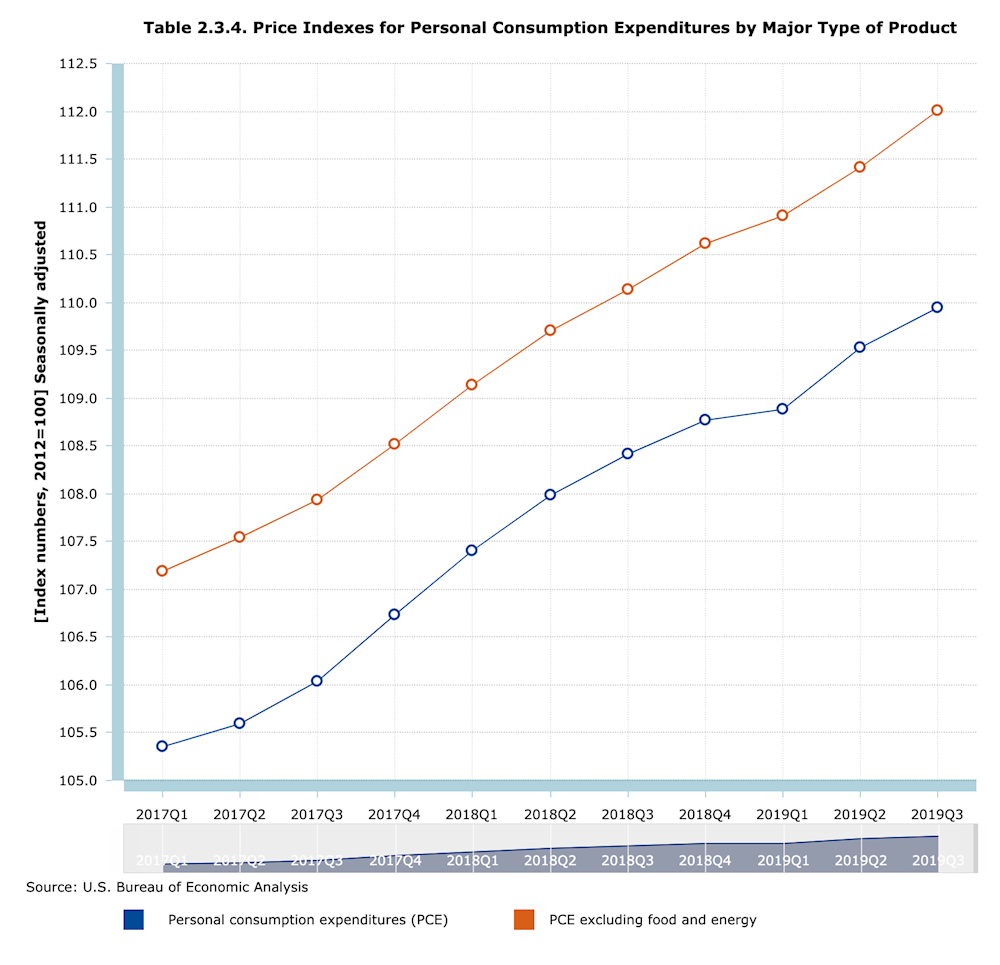

On a monthly basis, the U.S. government releases two widely accepted measures of inflation: the consumer price index (CPI) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Additionally, since 2007 two measures of PCE have become available: total PCE inflation rates and core PCE inflation rates, which omits food and energy (oil, gas, natural gas) due to their volatility. These indices draw on much of the same data but are different in scope, which offers the Fed a deeper understanding of the true inflation rate for the nation.

According to current forecasts, the 2019 year-end total (i.e. headline) PCE median rate of inflation is expected to be 1.5%. In 2020, this measure is expected to raise to 1.9% and then to 2.0% in 2021.

If these estimates hold true, the U.S. will hit its target inflation rate of 2% by 2021. This target is set by the Fed and, as mentioned earlier, is one of the essential measures that determine decisions on how and when to take action. For example, if the overall demand for goods and services is too strong, unemployment can fall to dangerously low levels and the core inflation rate becomes at risk of rising above the targeted 2%. In this case, the Fed may tighten monetary policy to increase interest rates which will slow down demand, force prices lower, and ultimately help stabilize the economy.

Domestic Policy Changes: Recent Changes to Keep an Eye On

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) was a major overhaul of the U.S. tax code and arguably the most significant of tax policy changes in three decades. A notable change was the reduction in the corporate tax rate from 34% to 21%, which was meant to incentivize business capital and expenditures that would eventually create more jobs. However, this change would also reduce corporate tax revenue, which is one of the major sources of revenue for the federal government; current estimates show a drop of about $61 billion from 2017.

As the fiscal health of the federal government continues to deteriorate, concerns about the impact and timing of this tax reform persist. Large increases in government expenditures, particularly spending on Social Security, Medicare, interest on our federal debt, defense, and infrastructure, all play a role in how these policy changes impact the economy in the long term.

Additionally, the president signed a new budget deal on August 2, 2019, which significantly increases the probability of a credit rating downgrade of the U.S. federal government. The new $2.7 trillion budget agreement is said to avert $126 billion in automatic spending cuts and suspend the debt ceiling through July 2021, according to a senior administration official.

Suspending the debt ceiling could prove to be a major flaw in this new deal. It could allow for significant spending increases during the upcoming electoral year, and the federal deficit is expected to hit $1 trillion sometime in late 2019 or early 2020. In looking at long-term forecasts, earlier this year the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the federal debt will reach an unprecedented 93% of GDP by 2093.

If credit rating agencies downgrade the U.S. federal government rating due to these imbalances, investors may be less willing to finance the government’s borrowing unless they receive higher interest rates, ultimately raising the government’s debt burden and prompting investors to pause due to the risks.

According to our recent report, this has created anxiety around U.S. bond yields (i.e. interest rates of bonds). Long-term bonds should yield more than short-term ones. However, the U.S. yield curve has inverted, meaning long-term bonds are yielding less than short-term bonds (two years or less) of the same credit quality. Historical patterns have shown an inverted yield curve to be an early indicator of economic vulnerability and possible recession. Yet with moderate inflation, low interest rates, some production capacity in manufacturing and continued growth in consumer spending, the current yield curve inversion does not “fit the mold” of a recession trigger, according to our recent report.

Climate Change: The Economic Impact of Severe Weather

Yes, even climate change can have negative effects on the U.S. and global economy.

As stated in our report, “although there is a high degree of uncertainty about the long-term economic effects of climate change and how they might play out, recent events demonstrate that the rise in average temperatures and sea levels can create adverse economic impact.”

Over the last couple of years, California has experienced mass devastation from wildfires. In 2017, wildfires destroyed more than 1.5 million acres, burning over 11,000 structures and costing the lives of 44 people, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. In 2018, more than 1.6 million acres were burned, over 23,000 structures damaged or destroyed, and 93 lives lost. This year’s California fire season has so far tallied 6,190 different incidents, 198,392 acres burned, and 3 fatalities.

In the Midwest, severe flooding has been a persistent problem for farmers up and down the Mississippi River, causing chaos with river transportation and the economy that depends on it. In an interview with NPR, one farmer stated, “It seems to get worse every year.”

In an article about how climate change can greatly impact the economy, The Balance wrote:

Scientists estimated that, if temperatures only rose 2° C, global gross domestic product would fall 15%. If temperatures rose by 3° C, global GDP would fall 25%. If nothing is done, temperatures will rise by 4° C by 2100. Global GDP would decline by more than 30% from 2010 levels. That's worse than the Great Depression, where global trade fell 25%. The only difference is that it would be permanent.

Climate change has caused more extreme weather around the globe and the rate of rising sea levels, which has increased in recent decades, has the potential to cause cascading severe effects that may impact where we live, where we work, and the health of America’s arts and culture.